Artful Possibility: Interview with Kansas City Ceramics Artist Andy Brayman

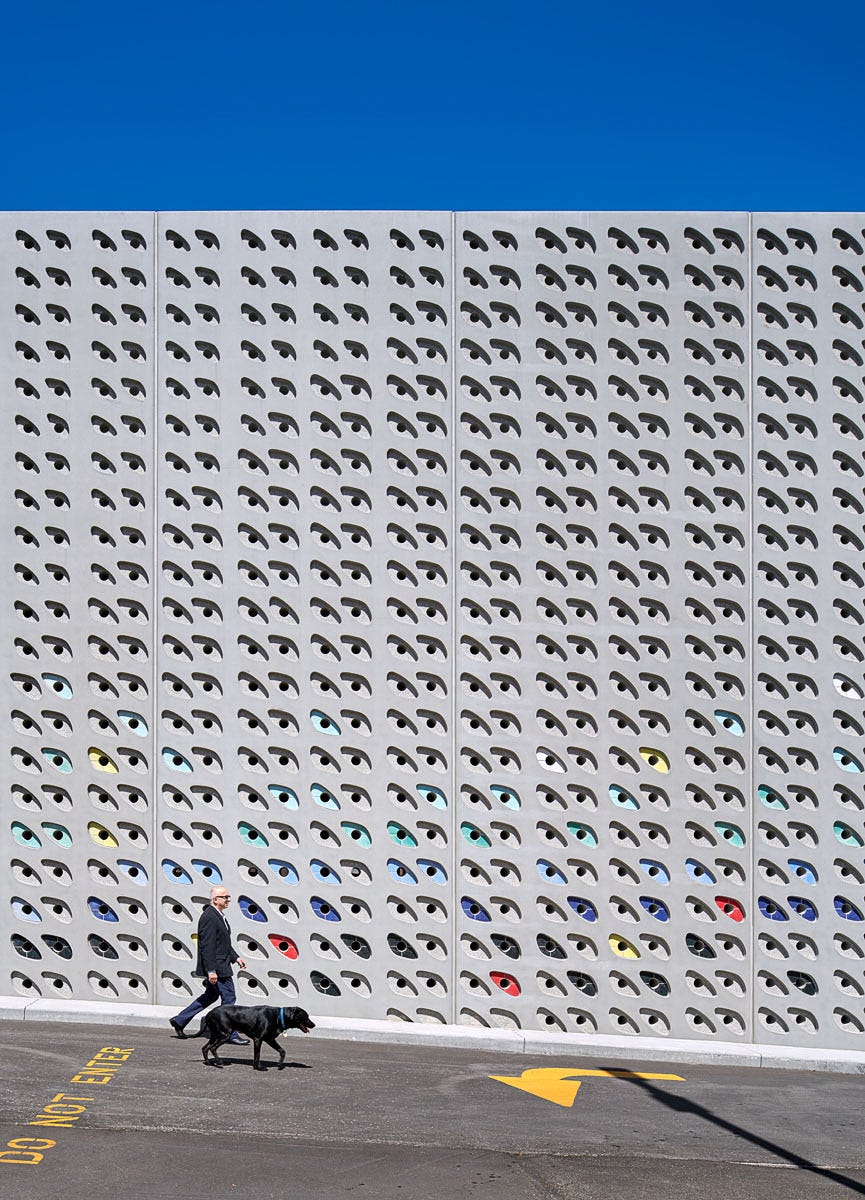

BNIM has revealed the artful possibilities of the parking structure through its work on the 10th and Wyandotte Garage, a collaboration with artist Andy Brayman. Andy is the founder of The Matter Factory, an Independence, Missouri-based studio for ceramics artists who integrate digital modeling and fabrication processes into their practices.

The garage is one of several projects BNIM has completed in this area of Kansas City’s urban core and allots space for another such project, the neighboring Crossroads Academy charter school, to create a small playground. Other work in the immediate area includes charter schools, multiple office developments, and cultural and performing arts centers.

Describe the work you do?

I am an artist who works mostly in ceramics. Ceramics tends to attract people who are almost Luddite in nature — physical material like clay is so primal, and less common than other mediums. On the other end of spectrum, I have been moving to a digital medium for some time; there has been a revolution in terms of tools, software, and inexpensive machines for fabrication.

My practice involves a lot of research that I hope leads to innovative processes. I work in between art and industry — my studio looks like a factory and my equipment looks like it should be in an industrial setting. I am interestingly positioned with an unusual knowledge in traditional art practices, and design using digital fabrication and software.

What has been your role in the collaboration with BNIM?

BNIM approached me to collaborate on the design of the building façades, and to create the ceramic art pieces embedded into specially designed indentations in the precast concrete walls.

What has been key to the success of this project with BNIM?

Public art can be pretty underwhelming, usually as a result of budget restrictions. BNIM did something cool and unusual by inviting me into the project at the front end. I was able to work side-by-side with the architects in the early stages, which enabled the art to be more integrated into the building.

What was the inspiration behind your creativity?

There’s a certain practicality with pottery. It is traditionally utilitarian, so the challenge is to make an object that is compelling in its functionality. It wasn’t difficult to adapt my strategy and process, because the garage is utilitarian by nature. There was one restriction: air flow into the building and the exhaust out. A certain percentage of the façade had to remain open per building codes and BNIM provided the information that helped me through that process. Elvis, you were the conduit to the bigger team and an amazing person to work with. It was a true collaboration.

Describe what you designed?

No one really likes parking garages, from which came the role of design and art. The challenge was to make the garage more interesting in the context of its downtown location. The artwork was designed first and is completely integrated into the building’s precast concrete walls.

To address the need for airflow — and daylight and views — we designed 4”-wide ventilation openings that respect both the size limit stipulated by building code and the grid of steel reinforcement in the precast concrete. The openings also create an aesthetically interesting pattern that is overlaid with a 2”-deep bas relief. The profile of the bas relief and inset ceramic tiles is a dimorphic, stretched-out oval — not a pattern I use much in my work. It was a direct result of input from BNIM, suggesting I try different shapes.

What did the process involve?

To create the façade, I worked with software that uses computer code to design patterns and write programs that show many different versions of a pattern. That software, interestingly, is used more by architects than artists. In a way, this became a common language and tool set between BNIM and me, allowing us to easily go back and forth.

How are the ceramic tiles you designed incorporated into the project?

I fabricated the tiles myself. The tiles for this project are not tiles in the traditional sense of a square affixed to a wall, but are a ceramic element set inside the oval shapes arrayed across the façade. These shapes occurs in four different sizes, laid out on the façades to approximate a gradient and provide movement. BNIM and I made the conscious decision for the ceramics to be the only rounded shape in the design, to contrast and soften the hard, orthogonal lines of the structure. We worked with engineers to determine where we could and could not put the shapes.

Can you describe the tiles?

We created a palette of eight colors for the ceramic tiles. They are visible from far away, and contrast with the color of the concrete to really “pop” off the building. Up close, there is a subtle pattern on the tile surfaces, providing visual interest from near and far.

Where and how are the tiles produced?

The tiles are made locally in my Kansas City studio, which is unusual and really tailored toward a new kind of digital fabrication. I use a C&C machine to create the “die” or mold. That mold went onto a 1940s hydraulic press — the furthest thing from digital. Ceramics must be made correctly for exterior use, to avoid breakage and other issues. I extensively researched making tiles that would bind for this climate, and created custom clay and glazes for this project.

I did this research in-house, where I also weighed, tested, produced, and fired the ceramics. The garage has 540 openings — ranging from the size of a lunch tray, down to something quite smaller. Each one of those has multiple ceramic elements inside, totaling more than 2000 tiles.

Posted to Medium