Material Matters: How Microbes, Mushrooms and Moss Could Redfine the Future Materials Library

If you are like me, you have gone down the grocery aisle with a list of trigger words in your head. Benzoate, corn syrup, partially hydrogenated, starch, monosodium glutamate, artificial flavor, sorbate, and just about anything else you can’t pronounce is likely to make you think twice about that bag of chips, box of cereal, or jar of pickles. The world of construction is likewise a minefield riddled with hazardous materials and processes — asbestos, formaldehyde, halogenated compounds, mercury, polyvinyl chloride, and so on. At every scale of design, we are faced with challenging considerations when selecting materials: cost, schedule, fire resistance, water resistance, thermal performance, durability, constructability, availability, and perhaps the most challenging — familiarity.

Like a nutrition facts label, product declarations and material safety data sheets are giving designers access to the ingredients that compose the materials they specify. This awareness is creating a demand for healthier buildings and healthier products.

As we strive to reach a wholly human-purposed design from every aspect, we look to emerging biological alternatives to the way we build.

MICHAEL LUCZAK | DEZEEN

Microbial Cellulose

When a symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) digests sugars and nutrients, it produces pure cellulose strands. These strands weave together tightly and form a resilient, translucent sheet that resembles fruit leather and is strong enough to be cut, shaped, and stitched. Experimentally, microbial cellulose is being explored for e-paper and OLED technologies and current applications include medical wound dressings, diaphragms for speakers, and the artist Suzanne Lee is even using microbial cellulose to create apparel. With these properties, could microbial cellulose be used for interior and furniture finishes, or an underlayment for green roof systems, or perhaps low-power digital wayfinding signage?

Mycelium

Mycelium is like the ‘root’ structure of fungus. It grows in spindly, branching filaments, tangling and binding organic material as it spreads. When mixed with shredded plant matter and wood chips, it can be molded and baked to take on a solid form. Companies like Ecovative are using mycelium for rigid insulation panels, particle boards, cushions, and molded packaging; and the process is simple enough that you can purchase a bag to grow yourself. Could mycelium be used to create SIPs free of chemical binders, or as a molded structural frame for furniture, or possibly as flooring substrates as a sound isolator?

Microbial Calcification

Certain microbes produce chemicals during their metabolic processes that create favorable conditions for calcification/mineralization. This happens in nature, where tidal bacteria at the water’s surface calcifies sand one layer at a time; the results are spectacular. BioMASON is a company that employs this natural system to produce bricks and there have been proposals to replace concrete with mixtures of aggregate and bacteria. Could microbial calcification be used for 3D printing complex structures, or creating structure underwater, or as landscape pavers and façade cladding panels?

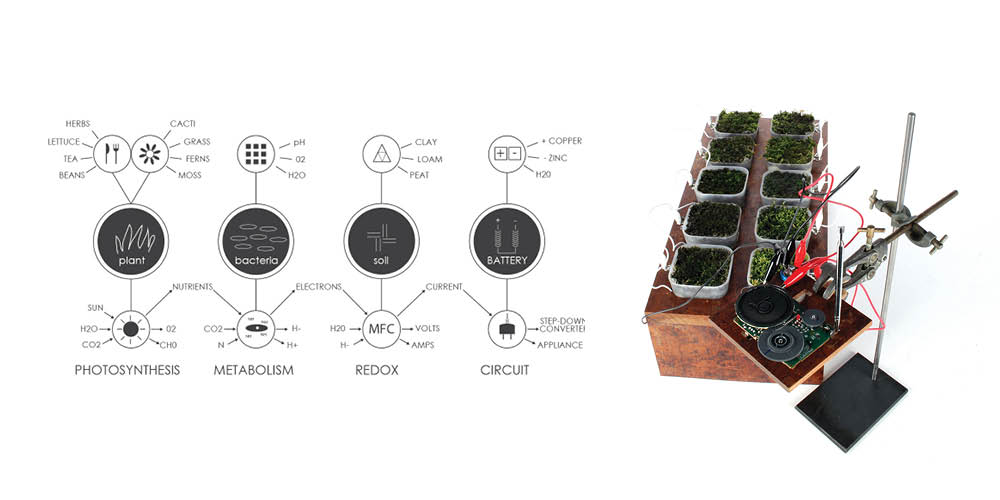

Bio-Photovoltaic

There are plants — typically moss or algae — that provide nutrients to feed bacteria. That bacteria then releases chemicals and free electrons, which can be used to create a voltage potential difference in an electrode. This is essentially a plant-based battery and is currently the focus of study for many students at the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC). Could entire green roofs generate power in addition to being beautiful gardens?

Just as the organic and local food initiatives are slowly removing our need to worry about the safety of the food we are buying, so too can the movement toward biomaterials eliminate our fears about the products that compose our environments. In order to truly achieve a design language that is restorative to the human condition, we need to embrace more creative — and possibly unexpected — biological systems.

Further Reading:

Movie Biocouture Microbes Clothing Wearable Futures from Dezeen

Ikea To Use Mushroom Based Packaging That Will Decompose In A Garden Within Weeks from True Activist

Bricks Grown from Bacteria from ArchDaily

Bio-Photovoltaic Panel from Design Book

Moss FM: The World’s First Plant-Powered Radio from FastCoExist

Bio-Photovoltaic System from the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC)